After the research study the following comments are my initial observations from the various building visits and conversations centred around the meaning of Brutalism to Brazil.

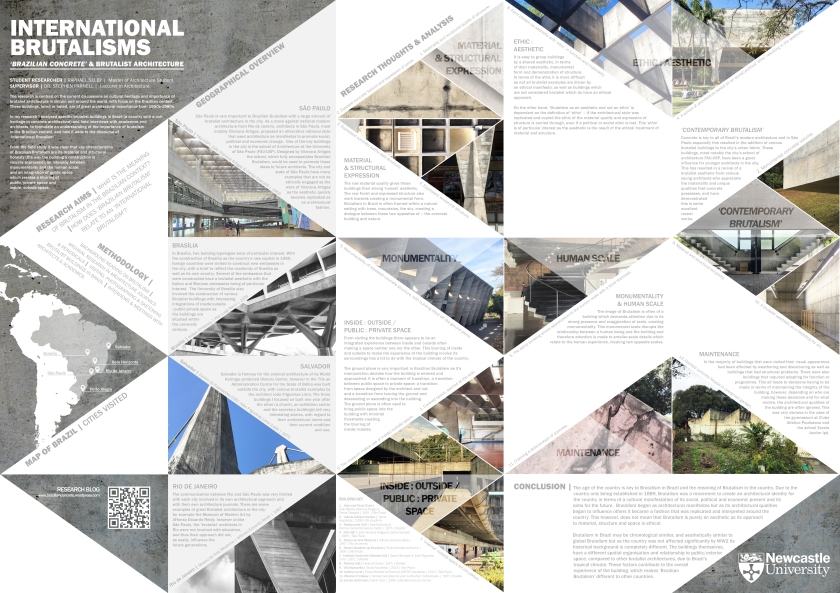

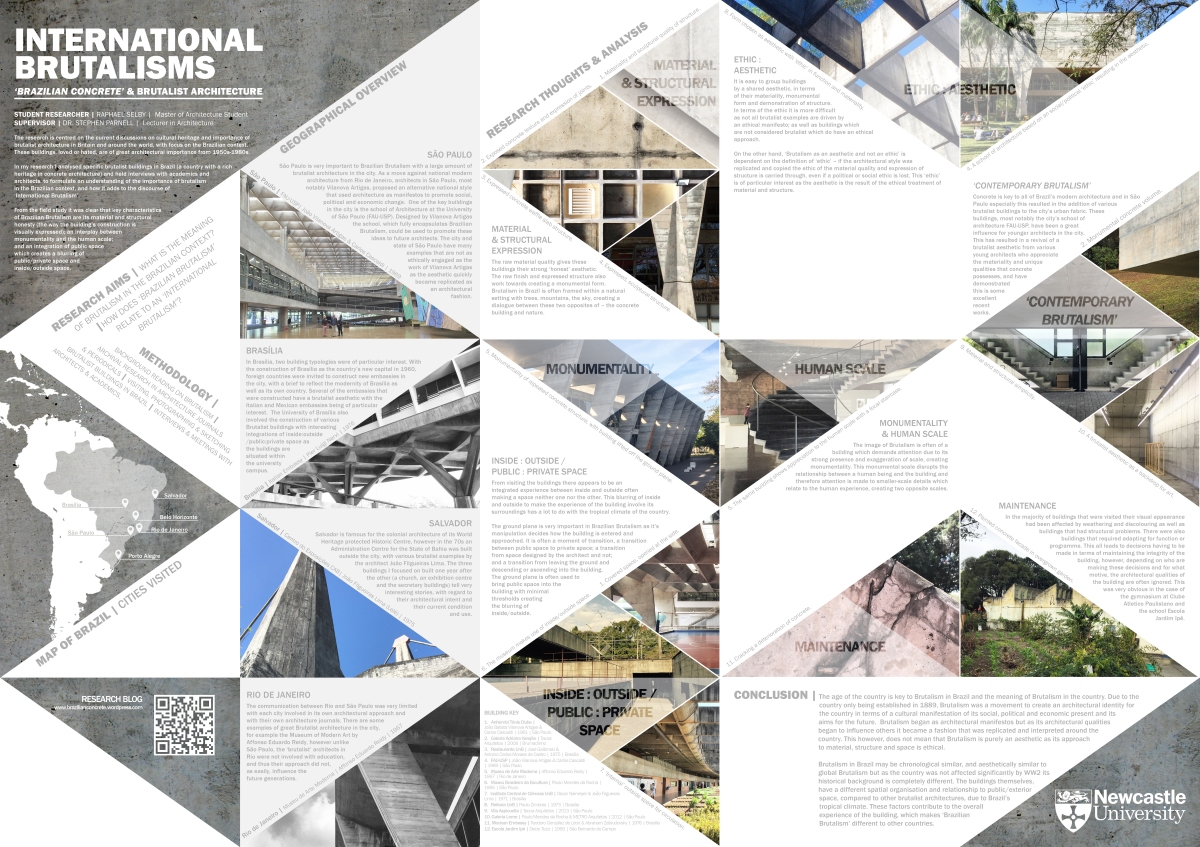

MATERIAL & STRUCTURAL EXPRESSION

The raw material quality gives these buildings their strong ‘honest’ aesthetic. The raw finish and expressed structure also work towards creating a monumental form of Brutalism in Brazil which is often framed within a natural setting with trees, mountains, the sky, creating a dialogue between these two opposites of – the concrete building and nature.

MONUMENTALITY / HUMAN SCALE

The image of Brutalism is often of a building which demands attention due to its strong presence and exaggeration of scale, creating monumentality. This monumental scale disrupts the relationship between a human being and the building and therefore attention is made to smaller-scale details which relate to the human experience, creating two opposite scales.

INSIDE:OUTSIDE / PUBLIC:PRIVATE

From visiting the buildings there appears to be an integrated experience between inside and outside often making a space neither one nor the other. This blurring of inside and outside to make the experience of the building involve its surroundings has a lot to do with the tropical climate of the country.

The ground plane is very important in Brazilian Brutalism as it’s manipulation decides how the building is entered and approached. It is often a moment of transition, a transition between public space to private space; a transition from space designed by the architect and not; and a transition from leaving the ground and descending or ascending into the building. The ground plane is often used to bring public space into the building with minimal thresholds creating the blurring of inside/outside.

ETHIC / AESTHETIC

It is easy to group buildings by a shared aesthetic, in terms of their materiality, monumental form and demonstration of structure. In terms of the ethic it is more difficult as not all brutalist examples are driven by an ethical manifesto; as well as buildings which are not considered brutalist which do have an ethical approach.

On the other hand, ‘Brutalism as an aesthetic and not an ethic’ is dependent on the definition of ‘ethic’ – if the architectural style was replicated and copied the ethic of the material quality and expression of structure is carried through, even if a political or social ethic is lost. This ‘ethic’ is of particular interest as the aesthetic is the result of the ethical treatment of material and structure.

‘CONTEMPORARY BRUTALISM’

Concrete is key to all of Brazil’s modern architecture and in São Paulo especially this resulted in the addition of numerous high-quality brutalist buildings to the city’s urban fabric. These buildings, most notably the city’s school of architecture FAU-USP, have been a great influence for younger architects in the city. This has resulted in a revival of a brutalist aesthetic from various young architects who appreciate the materiality and unique qualities that concrete possesses, and have demonstrated this is some excellent recent work.

MAINTENANCE

In the majority of buildings that were visited their visual appearance had been affected by weathering and discolouring as well as buildings that had structural problems. There were also buildings that required adapting for function or programme. This all leads to decisions having to be made in terms of maintaining the integrity of the building, however, depending on who are making these decisions and for what motive, the architectural qualities of the building are often ignored. This was very obvious in the case of the gymnasium at Clube Atletico Paulistano and the school Escola Jardim Ipê.

CONCLUDING THOUGHTS…

The age of the country is key to Brutalism in Brazil and the meaning of Brutalism in the country. Due to the country only being established in 1889, Brutalism was a movement to create an architectural identity for the country in terms of a cultural manifestation of its social, political and economic present and its aims for the future. Brutalism began as a manifesto but as its architectural qualities began to influence others it became a fashion that was replicated and interpreted around the country. This, however, does not mean that Brutalism is purely an aesthetic as its approach to material, structure and space is ethical.

Brutalism is Brazil may be chronological similar, and aesthetically similar to global Brutalism but as the country was not affected hugely by WW2 its historical background is completely different. The buildings themselves, mainly due to Brazil’s tropical climate, have a different organisation of space and relationship to public/exterior space, compared to brutalist architecture in the UK and other countries. The difference in space and therefore the experience of the building makes ‘Brazilian Brutalism’ different to other countries.